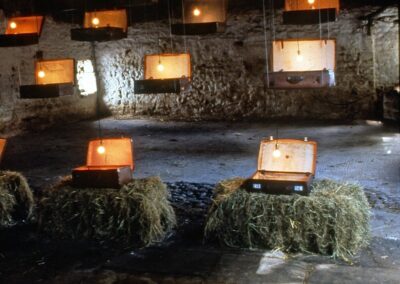

Multimedia installation by Russell Mills and Ian Walton

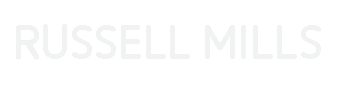

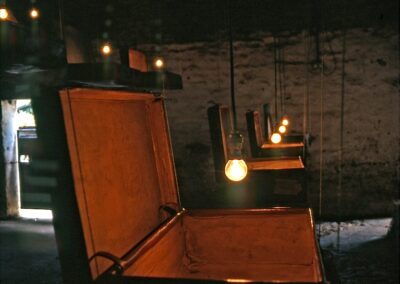

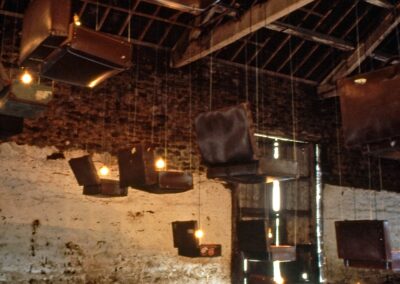

Lentworth Hall Farm Barn, the Forest of Bowland, Lancashire, for the ArtBarns: After Kurt Schwitters series of installations. 20 suitcases, hanging wires, hay bales, 20 40w globe light bulbs on random dimmer control, 1953 Philips Stella ST106A valve radio adapted for ceaseless random play

Soundwork mixed and produced by Russell Mills and Mike Fearon at Shed Studio, Ambleside, Cumbria

Still Moves

Lentworth House Farm, Abbeystead, The Forest of Bowland

Installation by Russell Mills and Ian Walton for ArtBarns: After Schwitters. 20 suitcases, hanging wires, hay bales, 20 x 40-watt globe lights on asynchronous dimmer control and the “Primum Mobile: This That There” (random radio) Lighting and technical installation by John Deakin (Stillpoint Productions). Radio adaptation by Alan Potter of Potter and Wightman, Kendal.

Still Moves was a work of homage, which focused on our responses to aspects of the life, works and influence of one of the most important figures of 20th-century art, the German artist Kurt Schwitters, who spent the last three years of his life (1945-48) in Ambleside, Cumbria. The installation also suggested ideas of transformation and regeneration, of movement between one state and another.

The use of old suitcases and travelling trunks relates to Schwitters’ peripatetic life. Prior to the rise of the National Socialist Party in Germany in the mid-1930s and the accompanying intolerance towards intellectuals, radicals and the intelligentsia, Schwitters had travelled extensively and freely in Europe. His love of travel instilled in him since his frequent childhood expeditions were later prompted by the need to escape from the stifling relationship with his parents. He wrote. “With both my parents in the same house, I’m simply conservative … you can only stand it if you travel a lot.” By train, bus and tram, Schwitters crisscrossed Europe to attend exhibitions, visit other artists and to tour his own brand of subversive, anarchic Dadaist performance with the founder of the De Stijl movement Theo Van Doesburg and others. On his journeys several close artistic friends acted as porters to carry the numerous suitcases he always insisted on taking with him. There are many anecdotal stories of these journeys, which reveal that the suitcases were generally full of materials for his collages and assemblages rather than any personal effects and clothes. Schwitters would stop abruptly, open cases, pull out scraps of collage material and create collages wherever and whenever the mood took him. Van Doesburg relates the tale of once racing to catch a train while struggling with a particularly heavy suitcase, which suddenly burst open, its contents spewing out over the pavement. Much to Van Doesburg’s annoyance, and everyone else’s amusement, the case was found to be full of heavy stones and rocks, nothing else.

Under the culturally restrictive Nazi regime, Schwitters’s travels became more dangerous and necessarily less frequent. Branded as a ‘Degenerate Artist’ and under the close scrutiny of the Gestapo, he was finally obliged to flee Germany in 1937, escaping to Norway with his son Ernst. After a few years of being holed-up in Lysaker eking out a pittance, as the Germans invaded Norway in 1940, he and Ernst were once again obliged to seek refuge. Managing to secure a passage on the last allied boat to leave Norway, they arrived in Scotland where they were immediately arrested as ‘Enemy Aliens’. They spent eighteen months being shifted from various detention camps in Mid-Lothian, Yorkshire, Lancashire and finally, in Schwitters’s case, on the Isle of Man.

On his release in 1941, he re-joined Ernst in London. Whilst there he befriended Edith Thomas who he nicknamed Wantee; she quickly became his partner and his muse. Finding living in London intolerable (the Blitz was at its height, food shortages were extreme and Schwitters found no support or sympathy for his work), they moved to Ambleside in Cumberland and Westmorland in 1945. Suitcases accompanied him on all these enforced journeys. They contained all that he had managed to salvage from each hasty escape, all that he held most precious. Other anecdotes survive which describe his ingenuity in using his suitcase to combat the weather even when infirm. During the severe winters of 1946-47 when he lived at 2 Gale Crescent, a house high up over the town, Schwitters would use his suitcase as a sledge to slide over the snow and ice down into Ambleside.

Rising from the floor towards the roof, twenty suitcases were suspended in a series of rising tiers. Appearing to float, defying gravity, they suggested aspiration, imagination and freedom.

Each was empty, open and over each was suspended a single, low voltage, bare light bulb glowing and dimming on a slow pulse. The only other element in the installation was the “Primum Mobile: This That There”, a 1940’s valve radio, which had been specially adapted to defy manual tuning, its internal tuner obliged to literally ‘travel’, ceaselessly trawling the wavebands, passing through station broadcasts and transmitting random fragments of sound in real-time. Visitors to the installation never heard the same sounds twice, as sounds of the every day, of what’s happening in the moment, stuttered and shrieked, slurred and slithered, into an audio collage, mirroring Schwitters’s own hybrid assemblages and the sonic experiments of his phonetic poems

The responses we received were intriguing and extremely gratifying, especially as Still Moves was sited in a barn in the middle of remote and vast open moorland. These rows of silent, empty suitcases, like an altar of votive lights, inspired a myriad of associations and emotions, some joyful, others painful and emotionally heightened. Memories of travel, to dreaded boarding schools, to the unknown horrors of war, or to distant lands in search of new beginnings, mingled with remembrances of the exhilarating anticipation of packing for holidays or the unbearable loss of loved ones. Ranging from the joyous to the painful, from the poignant to the aspirational, from the real to the metaphoric, these memory jolts triggered a wave of reflections on partings and meetings, on discovery, on yearning and on ghosts. One visitor, writing anonymously in the Visitors Comments Book, penned a poem, which as the extract below shows, expressed much of how many people felt on experiencing the installation:

… Inside the torn

lining of my box, clinging to ruched pockets and straps,

I sway to wavebands in random discharge, embracing you all,

wondering how long you have been empty of clothes

of greetings and goodbyes, of journeys that began and ended

on platforms, battered spectators as you were

to timetables and separations.

A suitcase is not only a simple means of transporting belongings, but is also a mirror of one’s personal expression. Cradling uniquely individual objects, which reflect the owner’s character, preferences and needs, the suitcase is literally a carrier of memories and meanings, rich in historical associations and dreams of possible futures. It suggests movements of individuals and of populations, made by choice, necessity or force. Symbolising transience and uncertainty, the suitcase conjoins memories of post-war trauma and mass migration following all wars and more topically, the multi-cultural diaspora of asylum seekers from the Eastern Baltic States into the rapidly expanding European Union.

The image of a suitcase, packed prior to a departure, conjures up a myriad of images and emotions: the wrench of separation and loss, or brave new beginnings and hopes for a brighter, better life. For some it represents a door opening onto unknown horizons and new experiences, or as a key to unlock a wider choice of opportunities that may eventually offer a chance of escape from the claustrophobia of the familiar and to shape one’s own identity without fear of repression.

Nomadic, it is an icon of reaction against the constraints of cultural and geographical limitations. Like a guerrilla army that is small, mobile and adaptable, as opposed to the lumbering machinations of a regular army, it recognises no boundaries or traditional rules. Signifying exile and displacement it is not merely a nostalgic trigger, a lazy cliché but rather is a potential constituent in a transitional flow, an in-between state.

It exemplifies Jacques Derrida’s phrase, half “not there” and half “not that. ” Equally apt is his summation that “the suitcase signifies the moment of rupture, the instance in which the subject is torn out of the web of connectedness that contained him or her through an invisible net of belonging.”