Multimedia installation by Russell Mills and Petulia Mattioli

Palazzo delle Papesse Centre for Contemporary Art, Siena, Italy

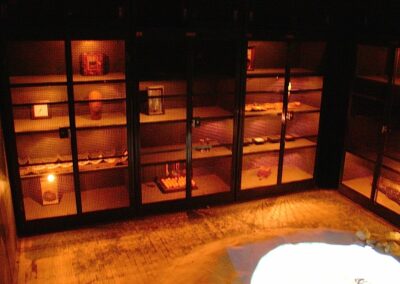

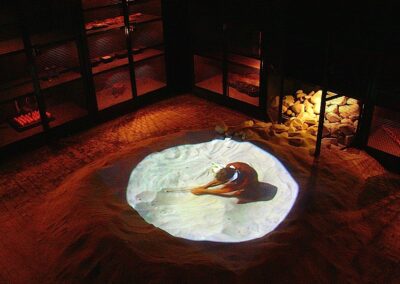

38 mixed media ‘thought engines’, 2 DVD films, 2 DVD projectors, stones, quartz sand, mirror, lighting, 2 CD players, 6 speakers

Soundwork by Eraldo Bernocchi, Russell Mills and Michael Fearon with contributions from Harold Budd, Bill Laswell and Gigi

Mixed and produced by Eraldo Bernocchi at Verba Corrige Production, Castagneto Carducci, Italy

Additional production by Russell Mills and Mike Fearon at Shed Studio, Ambleside, Cumbria

Palazzo delle Papesse

The Palazzo delle Papesse, originally known as the Palazzo Piccolomini, was built between 1460 and 1495, by order of Caterina Piccolomini, sister of Pope Pius II. It was here in 1633 that Galileo, following his trial for heresy that had been ordered by Pope Urban VIII, spent six months under house arrest. The controversial publication in 1632 of his Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (Dialogo Sopra i Due Massimi Sistemi del Mondo), which championed Copernican theory and a non-geocentric model of the solar system, had alienated him from both the Catholic Church and the Jesuits. In July 1633, after six months of questioning and following threats of torture by the Inquisition, Galileo was required to “abjure, curse and detest” his published opinions and was sentenced to formal imprisonment, his Dialogue was banned and publication of any of his extant or future works was forbidden.

The day after this trial the imprisonment order was commuted to house arrest, which he remained under until his death in 1642. Archbishop Ascanio II Piccolomini, a literary and scientific scholar, and friend and supporter of Galileo, offered him initial refuge in his home, the Palazzo Piccolomini. Galileo remained here for six months, in which time, while he continued his investigations, he forged valuable intellectual relations with numerous Siennese scholars, amongst them Archbishops, bishops and clergymen, who, seeking his knowledge would visit him discreetly under the cover of night. Galileo would take them up to the roof terrace where they observed the stars through his telescopes while he explained his transgressive theories.

The Caveau

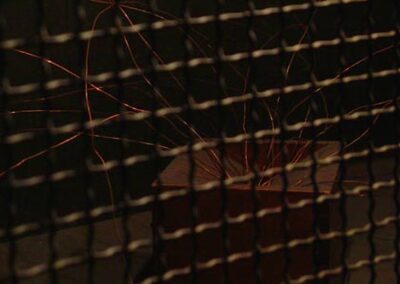

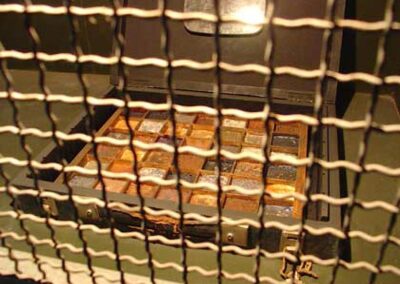

In 1884 the Palazzo was acquired to become the headquarters of the Bank of Italy, and in 1952 a strong room was constructed in its cellars. In 1998, after years of neglect, it became the Palazzo delle Papesse, the Centre for Contemporary Art. Since its inception, the strong room, still intact and with its original grilled iron cabinets and its huge, thick armoured safe door, has been used as a special project space for artists to experiment in and with. Known as the Caveau, it is no mere shell, but a challenging space that presents difficulties for any artist’s intervention, as any attempts to integrate works into the space run the risk of being overwhelmed by the room and its contents.

Alluding to the original purpose of the strong rooms, that of keeping objects safe and hidden, Mills and Mattioli developed various ideas about possession and revelation, about seeking and uncovering alternative readings and narratives in response to what is presented to us as knowledge, as truth.

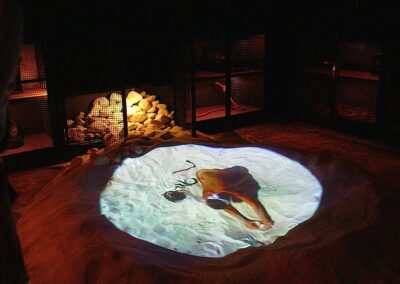

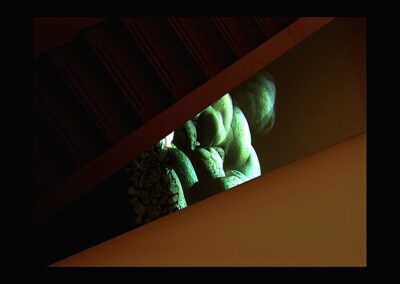

Mattioli created two allusive, conjoined films: one of smooth white rocks falling one after another, incrementally building a pile, an accumulation representing a search for knowledge and understanding. The second film shows a naked, blindfolded female kneeling on white sand, her fingers stretching out, feelseeing and clawing, with an energy that involves her whole body. Occasionally she digs out rocks or small objects. The rocks of the first film, symbols of permanence and certainty in an increasingly uncertain world, through natural erosion have become the impermanent sand and dust of the second. Disintegrating, they are emblematic of the slow passing of geological time and the fragmentation and complexity of our rapidly changing world.

The urgency of her action, the gesture itself, the act of searching rather than the finding, is fundamental. What is found is secondary to the search itself. Knowledge is reached through the senses; hands recognise through touch. The body becomes an antenna for the perception of the world and for its interpretation. Her nakedness and blind-seeking emphasises both the fragility and potential dangers of the information we receive and the fact that the knowledge we seek cannot be achieved without a capacity to risk. As tradition has it, blindness (in this case, temporary) reveals itself not so much as an allegory of darkness and emptiness, rather as a condition that can lead us more directly to knowledge, or at least to a heightened awareness.

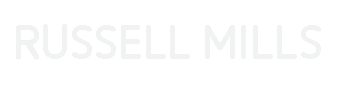

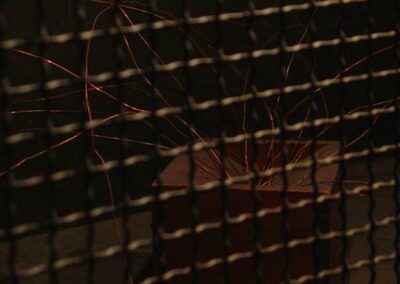

To complement Mattioli’s films, Mills created a series of 39 mixed media works, disparate couplings, called ‘Thought Engines’, object poems that act as metonymic metaphors, conceived to suggest new, unlikely relationships and correspondences.

Using everyday objects marked by use and the patina of time, suggestive of unknown distinct histories, individually they are oddly familiar. Yet when collectively placed in the iron cabinets of the vault, eased into improbable, enigmatic alliances with the other objects and with Mattioli’s film, they generated a sense of unease. Through juxtaposition and ambiguity, their meaning continually slides, eluding precise and easy interpretation. Cumulatively they reference the encyclopedic cabinets of wonder, the Kunstkammer (art-room) or the Wunderkammer (wonder-room) that first appeared in Renaissance Europe. Precursors of museums, these were regarded as microcosms or theatres of the world or as memory theatres.

Many of the ‘thought engines’ function as incubators of latent energy or act as talismanic emblems of certain values, beliefs and hopes that we all share or need to prioritise more than we do. Some are concerned with ideas of preciousness, not of rare or desirable things, but rather of essential, fundamental choices and preferences. Festina Lente, a clock that quietly sits counting time in the darkness, its face ambiguously showing thirteen hours, serves as a memento mori for a society that has become myopically obsessed with and increasingly distracted by the evanescent and the trivial.

Others are unashamed signifiers of potential, of what might be rather than what is or has been. Some, about the cycles of nature and the passing of time, were formulated to advocate the primacy of process and elicit ideas of transformation and regeneration. Others tackle beliefs and rites, superstitions and mythologies, referring to the differences between religious belief systems and natural phenomena, between invented myth and given fact. Several reference aspects of Galileo’s life and work and the effects of his discoveries, that challenged and dramatically overturned previous beliefs. Hold: The Deep Uncertainty of Knowing, is a large Victorian bible, its coal-black binding embedded with razor blades; too hazardous to grasp and its contents potentially too perilous to be revealed, it has been neutered by its own defence system.

Like oracles or mediums, they hide patiently, awaiting a response from us that, through a chain reaction of associative thoughts, may reveal their meanings. Whether critical of socio-political processes, religions or corporate ethics, or suggestive of more esoteric notions, hopefully they are all enabling.

Throughout the evolution of the collaboration, as most of its multiple meanings alluded to so many aspects of the ideas at work, the word ‘hold’ continually asserted itself, finally becoming the installation’s title, The notion of being held also became synonymous with the need to bind our individual ideas, and the diverse elements we were planning to use, in an intertwined dialogue.